Siobhan Hearne

I am currently writing my PhD thesis on female prostitution in late-imperial urban Russia, and I am particularly interested in how prostitutes, their clients and wider urban communities experienced, and resisted, the imperial system of regulated prostitution. As with most histories of lower-class people, and in particular histories of women, source material can be often difficult to come across. Primary sources from central administrative bodies, such as the imperial Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, are often heavily fragmented and tell us very little about the women who actually worked as prostitutes in this period. Because of this, I decided to incorporate more focused case studies of several smaller towns and cities into my research. This has allowed me to work in regional archives across the former Russian empire, where the material has been especially rich and varied in comparison to that of central archives in Moscow and St Petersburg.

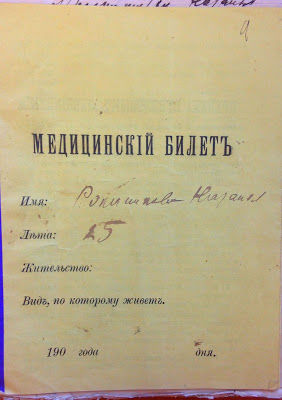

So, what exactly am I researching? The tsarist government installed a system of regulated prostitution in 1843, which remained in place until it was abolished by the Provisional Government in June 1917. Prostitutes were legally required to register their details with their local authorities, who then issued them with a medical ticket for identification. While registered, prostitutes were obliged to attend weekly gynaecological examinations in an attempt to prevent the spread of venereal diseases.

The regulation of prostitution was very much a regional endeavour. Although direction did come from central government in the form of circulars and decrees, provincial authorities were solely responsible for ensuring that regulation functioned correctly. Municipal authorities had a wide range of responsibilities, such as registering and removing of prostitutes from the police lists; keeping an up-to-date record of their sexual health and current address; granting licenses for the opening of brothels and conducting surveillance of women they believed to be working without a medical ticket.

Whenever I start working at a Russian archive, my first step is usually to locate the files of the organisations that policed prostitution, such as the medical-police committee (vrachebno-politseiskii komitet) or the city sanitary committee/bureau. These files usually give me personal information about the women who worked as prostitutes and hint at how prostitution fitted within wider urban communities.

In 1904, St Petersburg had the largest prostitute population in the Russian empire with 2844 women working in the commercial sex industry. The capital was followed by Warsaw with 1127 and Moscow with 1023. These figures show the difficulty of conducting research into individual prostitutes’ lives within these large economic centres. Instead, I chose smaller cities as case studies to show how regulation worked at a regional level. My first is the city of Arkhangelsk, which was home to just 23 prostitutes in 1909. As a busy commercial port and the economic centre of the largest province in European Russia, the city proved to be a very interesting case study.

The State Archive of Arkhangelsk Oblast (GAAO) had a wealth of material on prostitution, including detailed police lists of city prostitutes and over one hundred letters sent to the local police chief from prostitutes and brothel-keepers. Arkhangelsk’s modest prostitute population in the early twentieth century meant that I was able to trace the histories of individual women working in the city, and explore connections between prostitution and female migration patterns in the Russian North. It was in GAAO where I saw a prostitute’s medical identification papers in person for the first time.

Another of my most productive regional archival experiences was working at a branch of the Estonian National Archives in Tartu. This particular archive is home to an abundance of material on prostitution in early twentieth-century Revel’ (now Tallinn, the capital of Estonia). While working in Tartu, I was struck by the different types of sources that I came across, which ranged from huge files with hundreds of photographs of prostitutes to detailed court cases of individuals accused of procuring women for prostitution.

The Revel' medical-police committee also kept extremely detailed information about prostitutes in the city. Their police lists include information about: women’s nationality; their former city of residence; where and when they began working as prostitutes; and the name of the brothel in which they worked. This level of detail meant that I was able to draw conclusions about the unique composition of prostitutes in this area and explore how the regulation of prostitution worked differently across the Baltic provinces. Researching at smaller regional archives has proved instrumental in deepening my understanding of how the regulation of prostitution worked ‘on the ground’ in the late Russian empire. The material that I have found outside Moscow and St Petersburg has generally been more varied and a greater amount of documentation seems to have been preserved in provincial centres. This level of detail makes writing the history of a long-neglected group ever more fruitful.

State Archive of Arkhangelsk Oblast/Государственный Архив Архангельской области http://gaao29.ru/

National Archives of Estonia/Rahvusarhiiv Tartus http://www.arhiiv.ee/en/national-archives/